By Forrest Pritchard / November 23,

2015 /

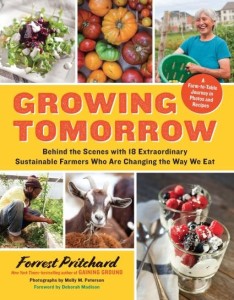

Forrest’s newest book has just come

out and it’s a beautiful thing! Click on over to the On Pasture bookstore to

learn more about it.

I’ve been raising grass

fed-and-finished beef for nearly twenty years, and I direct market 125 head of

slaughter steers and heifers each year through local farmers’ markets. These

animals are 100% pasture finished, averaging 1250 lbs live weight at 24 months

of age. All the while, our farm maintains a rolling herd that averages close to

200 stockers, along side of 250 ewes and lambs. As each year passes—10 months

of daily, rotational mob grazing, as well as feeding two months worth of

hay—our pastures continue to steadily improve, increasing our ability to

comfortably (yet conservatively) increase stocking numbers. Hey, it’s a

beautiful thing.

That we accomplish this on 500 acres

of pure pasture, with 35 inches of annual rainfall and limestone soils, might

seem extraordinary to some, and perhaps not that surprising to others. But

every farm is different, just as every manager has different skill sets, and

every herd of cattle will have its superior genetics, mixed with inferior

animals. To wit, there are hundreds of operations within a half hour’s drive of

my farm that have the same advantages as us, yet produce a fraction as much

beef. Like most things in life, it’s not about the potential, it’s about the

execution.

Becoming a full-time, professional

grass-finished farmer is a lifelong process, and multiple moving targets is a

daily fact of life. As such, advice that works well on one farm might have

little bearing on a different farm just down the road, much less on acreage

that receives only 15 inches of annual rainfall. Armed with that perspective,

here are 3 tips that I think should apply to any and every grass farm, viewed

through the kaleidoscope of pasture-finished beef in particular.

Don’t

Shortcut the Process

Here’s a past On Pasture article

with a video showing what you can look for to know that your cattle are

finished. Just click on over.

One of the worst (and most

shortsighted) things I can do is harvest a steer before it is “finished”. By

this, I mean the animals need to be at LEAST 1150 pounds live weight before

I’ll even consider putting them on the trailer to the butcher, and preferably

more than 1200. This past summer, our average slaughter weight (we haul 4

beeves at a time) was just under 1250 lbs. As a direct-marketer, this is

important for two big reasons.

One, the difference between a 1,000

pound steer and a 1,250 pound steer might not seem like much when they are

standing side by side in the pasture, but from a yield perspective (1,000 X

0.39 bone-in yield = 390 lbs finished product; 1250 X 0.39 bone-in yield =

487.5 lbs finished product), a difference of 97.5 lbs of product per animal is

tremendous. For example, at $8/lb, this translates $780 per head. During the

course of a year, where I process roughly 125 animals, this adds up to a

whopping $97,000! With average daily gains of 2.5 lbs on our farm, this

requires an extra 100 days of grazing, not to mention some advance planning.

But $780 per animal is a powerful economic incentive to find ways to keep that

steer grazing.

The second reason is this: Taste and

tenderness. The eating experience that comes from a ribeye (for example) on a

properly finished steer, versus an under finished steer, is unparalleled. For a

one-inch thick steak, this is the difference between a richly marbled 13 oz

ribeye, and an 8 oz steak with perhaps a quarter inch rind of fat, but little

else to provide flavor. Which steak do you imagine your customers will enjoy

more, and which will bring them back to your farm?

Feed

Animals To Make Money, Not Save Money

One of the best decisions I ever

made was to stop making hay, and start buying it. Was I nervous at first? Sure!

But once I did it, I’ve never looked back. Here’s why.

These are Troy Bishopp’s dairy

heifers grazing stockpile. Great minds think alike! (Photo by Troy Bishopp)

For one, by not cutting hay, it

allows our pastures to fully flourish both above ground and below. This

provides surface biomass for the cattle to eat (and equally importantly, to

trample), as well as greatly expands root mass below. Extra root mass adds

critical organic matter to help trap rainfall and build soil structure,

creating microbial habitat and increasing rain infiltration rates. Moreover, by

not making hay all summer long, it allowed us to focus on intensified management

of the cattle, creating mob-grazing subdivisions (more than 100,000 lbs beef

per acre, for 12 hour shifts) from May through September when the grass is

especially thick.

What happens during winter? I’m glad

you asked! Once the pastures go dormant around mid November, we stretch our

stockpiled pastures well into January. How do we have stockpiles? Primarily as

a result of not cutting the pastures for hay (see the pattern here?). We then

feed locally sourced hay from February through March on depleted pastures,

unrolling the round bales, spreading seeds and feed. This not only nourishes

our cattle, but the pastures as well.

The bottom line: By buying all our

hay (we typically pay $60 per 800 lb. roll, delivered), as well as by

eliminating equipment costs, we’re actually MAKING money on both the front end

and back. We accelerate future soil fertility by rotating cattle all summer,

extending our fall grazing season, and then fertilizing (while feeding) all

winter long.

Change

How You Look At Your Pastures

Perspective is everything in this

type of farming. Remember, you are a grass-farmer… not a cow farmer, or a sheep

farmer, or—I shudder at the thought—a hay farmer. After all, it’s our pastures

(and our soils) that are our true generators of revenue, are they not? With

this shift in perspective, I think it’s especially helpful to regard our

pastures as we would our gardens, with the grasses, legumes and livestock as

the “crops”.

For example, would you drive a

pickup truck through your garden? Of course not! So why would you do that to

your pasture? Just like in a garden, it compacts soil, crushes our “crop” of

pasture and—in many cases—facilitates erosion. As another example, would you

fertilize your garden with compost and cover crops, or would you leave the soil

to fend for itself, hoping that “somehow” fertility will increase? Naturally,

you would fertilize it. And it’s precisely by using that which nature gives us

for free—namely, sunshine, carbon, nitrogen and rain—we can manage our animals

to be our chief fertility experts. On our farm, they eat 30%, trample 70%, and

poop on ALL of it!

Lastly, no one would let a cow into

his garden, even for a minute. And for good reason… they’d eat everything up in

seconds flat! But the same common-sense idea pertains to our pastures. Yes, we

want our cattle to eat (see point #1 above). But much like picking a tomato or

a few leaves of lettuce—and not yanking up the entire plant, or harvesting it

down to the soil— we want the cattle to eat just enough to nourish them, before

moving on.

Why? Just like in a garden, this

allows for the most nutritious bites, reduces parasite exposure, and provides

ample time for vegetative recovery. Suffice to say, when I started thinking

about my pastures as I do my garden, my entire perspective shifted. Good things

followed!

Want to know more? Check out my New

York Times bestselling book, Gaining

Ground, where I detail the step-by-step process of becoming a

professional grass farmer. AND see my latest book, Growing

Tomorrow for more stories about some of your fellow successful

farmers.

Thanks to the National Grazing Lands Coalition for making

this article possible. Click on over to see the great work they do for all of us.

Thank them for supporting On Pasture by liking their facebook page.

3 (Unexpected) Tips for Grass-Fed Success

Forrest’s

newest book has just come out and it’s a beautiful thing! Click on over

to the On Pasture bookstore to learn more about it.

That we accomplish this on 500 acres of pure pasture, with 35 inches of annual rainfall and limestone soils, might seem extraordinary to some, and perhaps not that surprising to others. But every farm is different, just as every manager has different skill sets, and every herd of cattle will have its superior genetics, mixed with inferior animals. To wit, there are hundreds of operations within a half hour’s drive of my farm that have the same advantages as us, yet produce a fraction as much beef. Like most things in life, it’s not about the potential, it’s about the execution.

Becoming a full-time, professional grass-finished farmer is a lifelong process, and multiple moving targets is a daily fact of life. As such, advice that works well on one farm might have little bearing on a different farm just down the road, much less on acreage that receives only 15 inches of annual rainfall. Armed with that perspective, here are 3 tips that I think should apply to any and every grass farm, viewed through the kaleidoscope of pasture-finished beef in particular.

Don’t Shortcut the Process

Here’s

a past On Pasture article with a video showing what you can look for to

know that your cattle are finished. Just click on over.

One, the difference between a 1,000 pound steer and a 1,250 pound steer might not seem like much when they are standing side by side in the pasture, but from a yield perspective (1,000 X 0.39 bone-in yield = 390 lbs finished product; 1250 X 0.39 bone-in yield = 487.5 lbs finished product), a difference of 97.5 lbs of product per animal is tremendous. For example, at $8/lb, this translates $780 per head. During the course of a year, where I process roughly 125 animals, this adds up to a whopping $97,000! With average daily gains of 2.5 lbs on our farm, this requires an extra 100 days of grazing, not to mention some advance planning. But $780 per animal is a powerful economic incentive to find ways to keep that steer grazing.

The second reason is this: Taste and tenderness. The eating experience that comes from a ribeye (for example) on a properly finished steer, versus an under finished steer, is unparalleled. For a one-inch thick steak, this is the difference between a richly marbled 13 oz ribeye, and an 8 oz steak with perhaps a quarter inch rind of fat, but little else to provide flavor. Which steak do you imagine your customers will enjoy more, and which will bring them back to your farm?

Feed Animals To Make Money, Not Save Money

One of the best decisions I ever made was to stop making hay, and start buying it. Was I nervous at first? Sure! But once I did it, I’ve never looked back. Here’s why.

These are Troy Bishopp’s dairy heifers grazing stockpile. Great minds think alike! (Photo by Troy Bishopp)

What happens during winter? I’m glad you asked! Once the pastures go dormant around mid November, we stretch our stockpiled pastures well into January. How do we have stockpiles? Primarily as a result of not cutting the pastures for hay (see the pattern here?). We then feed locally sourced hay from February through March on depleted pastures, unrolling the round bales, spreading seeds and feed. This not only nourishes our cattle, but the pastures as well.

The bottom line: By buying all our hay (we typically pay $60 per 800 lb. roll, delivered), as well as by eliminating equipment costs, we’re actually MAKING money on both the front end and back. We accelerate future soil fertility by rotating cattle all summer, extending our fall grazing season, and then fertilizing (while feeding) all winter long.

Change How You Look At Your Pastures

Perspective is everything in this type of farming. Remember, you are a grass-farmer… not a cow farmer, or a sheep farmer, or—I shudder at the thought—a hay farmer. After all, it’s our pastures (and our soils) that are our true generators of revenue, are they not? With this shift in perspective, I think it’s especially helpful to regard our pastures as we would our gardens, with the grasses, legumes and livestock as the “crops”.For example, would you drive a pickup truck through your garden? Of course not! So why would you do that to your pasture? Just like in a garden, it compacts soil, crushes our “crop” of pasture and—in many cases—facilitates erosion. As another example, would you fertilize your garden with compost and cover crops, or would you leave the soil to fend for itself, hoping that “somehow” fertility will increase? Naturally, you would fertilize it. And it’s precisely by using that which nature gives us for free—namely, sunshine, carbon, nitrogen and rain—we can manage our animals to be our chief fertility experts. On our farm, they eat 30%, trample 70%, and poop on ALL of it!

Lastly, no one would let a cow into his garden, even for a minute. And for good reason… they’d eat everything up in seconds flat! But the same common-sense idea pertains to our pastures. Yes, we want our cattle to eat (see point #1 above). But much like picking a tomato or a few leaves of lettuce—and not yanking up the entire plant, or harvesting it down to the soil— we want the cattle to eat just enough to nourish them, before moving on.

Why? Just like in a garden, this allows for the most nutritious bites, reduces parasite exposure, and provides ample time for vegetative recovery. Suffice to say, when I started thinking about my pastures as I do my garden, my entire perspective shifted. Good things followed!

Want to know more? Check out my New York Times bestselling book, Gaining Ground, where I detail the step-by-step process of becoming a professional grass farmer. AND see my latest book, Growing Tomorrow for more stories about some of your fellow successful farmers.

0 comments:

Post a Comment