skip to main |

skip to sidebar

A stiff new layer in Earth’s mantle? Earth’s interior hotter than previously believed

March 2015 – GEOLOGY –

By crushing minerals between diamonds, a University of Utah study

suggests the existence of an unknown layer inside Earth: part of the

lower mantle where the rock gets three times stiffer. The discovery may

explain a mystery: why slabs of Earth’s sinking tectonic plates

sometimes stall and thicken 930 miles underground. The findings —

published today in the journal Nature Geoscience — also may

explain some deep earthquakes, hint that Earth’s interior is hotter than

believed, and suggest why partly molten rock or magmas feeding

mid-ocean-ridge volcanoes such as Iceland’s differ chemically from

magmas supplying island volcanoes like Hawaii’s. “The Earth has many

layers, like an onion,” says Lowell Miyagi, an assistant professor of

geology and geophysics at the University of Utah. “Most layers are

defined by the minerals that are present. Essentially, we have

discovered a new layer in the Earth. This layer isn’t defined by the

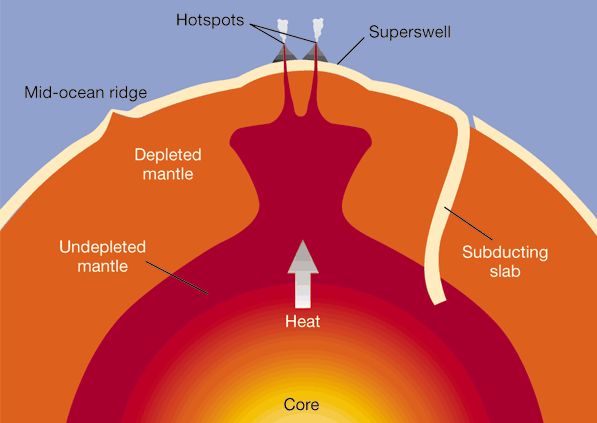

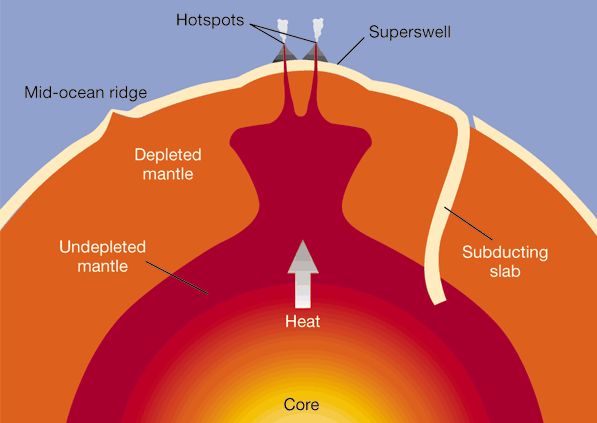

minerals present, but by the strength of these minerals.” Earth’s main

layers are the thin crust 4 to 50 miles deep (thinner under oceans,

thicker under continents), a mantle extending 1,800 miles deep and the

iron core. But there are subdivisions. The crust and some of the upper

mantle form 60- to 90-mile-thick tectonic or lithospheric plates that

are like the top side of conveyor belts carrying continents and

seafloors.

Oceanic plates collide head-on with

continental plates offshore from Chile, Peru, Mexico, the Pacific

Northwest, Alaska, Kamchatka, Japan and Indonesia. In those places, the

leading edge of the oceanic plate bends into a slab that dives or

“subducts” under the continent, triggering earthquakes and volcanism as

the slabs descend into the mantle, which is like the bottom part of the

conveyor belt. The subduction process is slow, with a slab averaging

roughly 300 million years to descend, Miyagi estimates. Miyagi and

fellow mineral physicist Hauke Marquardt, of Germany’s University of

Bayreuth, identified the likely presence of a superviscous layer in the

lower mantle by squeezing the mineral ferropericlase between gem-quality

diamond anvils in presses. They squeezed it to pressures like those in

Earth’s lower mantle. Bridgmanite and ferropericlase are the dominant

minerals in the lower mantle. The researchers found that

ferropericlase’s strength starts to increase at pressures equivalent to

those 410 miles deep — the upper-lower mantle boundary — and the

strength increases threefold by the time it peaks at pressure equal to a

930-mile depth.

And when they simulated how

ferropericlase behaves mixed with bridgmanite deep underground in the

upper part of the lower mantle, th ey

calculated that the viscosity or stiffness of the mantle rock at a

depth of 930 miles is some 300 times greater than at the 410-mile-deep

upper-lower mantle boundary. “The result was exciting,” Miyagi says.

“This viscosity increase is likely to cause subducting slabs to get

stuck — at least temporarily — at about 930 miles underground. In fact,

previous seismic images show that many slabs appear to ‘pool’ around 930

miles, including under Indonesia and South America’s Pacific coast.

This observation has puzzled seismologists for quite some time, but in

the last year, there is new consensus from seismologists that most slabs

pool.” How stiff or viscous is the viscous layer of the lower mantle?

On the pascal-second scale, the viscosity of water is 0.001, peanut

butter is 200 and the stiff mantle layer is 1,000 billion billion (or 10

to the 21st power), Miyagi says.

ey

calculated that the viscosity or stiffness of the mantle rock at a

depth of 930 miles is some 300 times greater than at the 410-mile-deep

upper-lower mantle boundary. “The result was exciting,” Miyagi says.

“This viscosity increase is likely to cause subducting slabs to get

stuck — at least temporarily — at about 930 miles underground. In fact,

previous seismic images show that many slabs appear to ‘pool’ around 930

miles, including under Indonesia and South America’s Pacific coast.

This observation has puzzled seismologists for quite some time, but in

the last year, there is new consensus from seismologists that most slabs

pool.” How stiff or viscous is the viscous layer of the lower mantle?

On the pascal-second scale, the viscosity of water is 0.001, peanut

butter is 200 and the stiff mantle layer is 1,000 billion billion (or 10

to the 21st power), Miyagi says.

Slab subduction triggers earthquakes and volcanoes

For the new study, Miyagi’s funding

came from the U.S. National Science Foundation and Marquardt’s from the

German Science Foundation. “Plate motions at the surface cause

earthquakes and volcanic eruptions,” Miyagi says. “The reason plates

move on the surface is that slabs are heavy, and they pull the plates

along as they subduct into Earth’s interior. So anything that affects

the way a slab subducts is, up the line, going to affect earthquakes and

volcanism.” He says the stalling and buckling of sinking slabs at due

to a stiff layer in the mantle may explain some deep earthquakes higher

up in the mantle; most quakes are much shallower and in the crust.

“Anything that would cause resistance to a slab could potentially cause

it to buckle or break higher in the slab, causing a deep earthquake.”

Miyagi says the stiff upper part of the lower mantle also may explain

different magmas seen at two different kinds of seafloor volcanoes.

Recycled crust and mantle from old

slabs eventually emerges as new seafloor during eruptions of volcanic

vents along midocean ridges — the rising end of the conveyor belt. The

magma in this new plate material has the chemical signature of more

recent, shallower, well-mixed magma that had been subducted and erupted

through the conveyor belt several times. But in island volcanoes like

Hawaii, created by a deep hotspot of partly molten rock, the magma is

older, from deeper sources and less well-mixed. Miyagi says the viscous

layer in the lower mantle may be what separates the sources of the two

different magmas that supply the two different kinds of volcanoes. –Science Daily

ey

calculated that the viscosity or stiffness of the mantle rock at a

depth of 930 miles is some 300 times greater than at the 410-mile-deep

upper-lower mantle boundary. “The result was exciting,” Miyagi says.

“This viscosity increase is likely to cause subducting slabs to get

stuck — at least temporarily — at about 930 miles underground. In fact,

previous seismic images show that many slabs appear to ‘pool’ around 930

miles, including under Indonesia and South America’s Pacific coast.

This observation has puzzled seismologists for quite some time, but in

the last year, there is new consensus from seismologists that most slabs

pool.” How stiff or viscous is the viscous layer of the lower mantle?

On the pascal-second scale, the viscosity of water is 0.001, peanut

butter is 200 and the stiff mantle layer is 1,000 billion billion (or 10

to the 21st power), Miyagi says.

ey

calculated that the viscosity or stiffness of the mantle rock at a

depth of 930 miles is some 300 times greater than at the 410-mile-deep

upper-lower mantle boundary. “The result was exciting,” Miyagi says.

“This viscosity increase is likely to cause subducting slabs to get

stuck — at least temporarily — at about 930 miles underground. In fact,

previous seismic images show that many slabs appear to ‘pool’ around 930

miles, including under Indonesia and South America’s Pacific coast.

This observation has puzzled seismologists for quite some time, but in

the last year, there is new consensus from seismologists that most slabs

pool.” How stiff or viscous is the viscous layer of the lower mantle?

On the pascal-second scale, the viscosity of water is 0.001, peanut

butter is 200 and the stiff mantle layer is 1,000 billion billion (or 10

to the 21st power), Miyagi says.

0 comments:

Post a Comment